John Ralston Saul reflects on Canada’s relationship with its Indigenous peoples

John Ralston Saul’s interest in Indigenous people dates back further than 2008, when he published A Fair Country, the book in which he argued that Canada is a Métis nation, heavily influenced and shaped by Aboriginal ideas.

Not everyone knows that Ralston Saul has been interested in Canada’s Indigenous peoples for four decades.

In the spring of 1976, when the respected intellectual and award-winning writer was 29, he travelled to Inuvik and the High Arctic Islands as an assistant to Maurice Strong, the founding chair and CEO of Petro-Canada.

The trip was nothing short of eye opening for Ralston Saul, who had just spent seven years in France, first earning a PhD and then running a small investment firm in Paris. He thought he understood Canada, but in listening to the Indigenous peoples that he and Strong met with, he realized he didn’t.

“(They were) making arguments I’d never heard (before),” Ralston Saul said. “They weren’t talking for or against, they weren’t talking romantically about nature the way southerners do. And I realized that I’d been deeply lied to—that my education had not prepared me for the reality of my own country.”

Since that experience, Ralston Saul has sought to better understand Canadian history and draw awareness to Indigenous issues.

His most recent book, 2014’s The Comeback, calls on readers to embrace and support the comeback of Indigenous peoples, and highlights the need to rebuild relationships with them

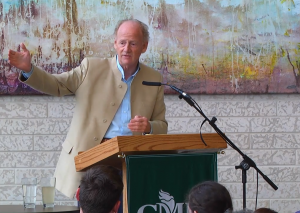

Ralston Saul travelled to Winnipeg last month to talk about the book with students in the course “Reconciling Our Future: Stories of Kanata and Canada” at Canadian Mennonite University’s (CMU) Canadian School of Peacebuilding (CSOP).

Ralston Saul came at the invitation of his friend, Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair, who taught the course.

During his visit to CMU, Ralston Saul also gave a public lecture at the university exploring immigration that drew a capacity crowd.

“What’s happening all over the country at a growing rate is that Canadians who were totally ignorant on Indigenous issues are gradually becoming less ignorant,” Ralston Saul said in an interview prior to the lecture.

He credits courses and books taught and written by Indigenous people with leading the charge.

“I’m kind of the exception to the rule that in the new wave, there aren’t that many non-Indigenous people that are writing in the nonacademic world,” he said.

He added that he has always been careful to write neither to, nor for, Indigenous people. If anything, he is writing to a non-Indigenous audience.

“I use my voice to say, Wake up guys. There’s a life and it’s got the word ‘Indigenous’ written all over it. So, you better wake up.”

Ralston Saul likens publishing A Fair Country to leaping off a “great, big diving board.” Given the nature of the book’s ideas, he thought it could be the end of his career.

Instead, he was thrilled to see Indigenous people embracing it.

He recalls talking about the book with Indigenous young people in Rainy River, a town in northwestern Ontario.

“(That was) very exciting because I think that so much of Canada is in the south, written by the south, for the south, and there’s a real denial of two-thirds to three-quarters of the country,” he said.

Before writing The Comeback, Ralston Saul wasn’t planning to return to the topic of Indigenous affairs. In fact, he had an entirely different book planned.

Still, he woke up one day with the feeling that he had to write something before the 2015 federal election that expressed his belief that rebuilding right relationships with Canada’s Indigenous peoples was of utmost importance.

“I had to intervene in the election as a writer to say that for me, and I think for the country, this is the single most important issue, and people should be voting on the basis of how the political parties stood on this issue,” he said.

He is pleased that Canadians voted in a government that says that it believes that the Indigenous question, unresolved as it is, is the single most important issue in Canada.

“We’ve come a long way, (us) non-Aboriginals,” Ralston Saul said. When it comes to these topics, there’s momentum now. “Suddenly, it’s moving. We have to make sure it keeps moving.”